About Me

Education, Professional Career and Volunteering

My Story

Born and raised in Sydney, I drew and painted from a young age and was fortunate to have parents who encouraged me to be creative. Trained in Sydney at the National Art School and University of NSW, I later completed two Masters’ degrees, and a Doctor of Education degree. My forty-year professional career involved visual arts teaching, teacher education and consultancy.

After retiring in 2008, my passion for native plants led me to focus on botanical art. Since then, along with my art making, I have been a volunteer in various organisations in NSW and Queensland, undertaking tasks like plant propagation, bush regeneration, coordination of the Bowral Art Gallery Botanical Art Group and editor of the Tendrils newsletter. From 2019 to 2021 I coordinated and illustrated the new “A Guide to the Robertson Rainforest”(REPS, 2021).

In Queensland I joined the Friends of the Gold Coast Regional Botanic Gardens, working at first in the Herbarium and the following year as Coordinator for the Friends Botanical Art Group (FBAG). As a member of Native Plants Queensland (NPQ) Gold Coast Branch, I have provided illustrations of rare plants and taught botanical drawing workshops for their members.

My exhibition history has seen my work shown widely in NSW in the Southern Highlands, Illawarra and Shoalhaven regions, in Sydney and Canberra at the Australian National Botanic Gardens and more recently in Queensland. My work is held in private collections in Australia, UK and Europe.

I now exhibit each year in the Gold Coast and in 2024 in Maleny in Queensland. One of my paintings was selected for the Botanical Art Society of Australia’s “Bountiful Botanicals: A Botanical Art Worldwide” Exhibition 2025 in Canberra.

Banner image: Eucalyptus aquatica, watercolour

What motivates my art making

I am driven by two life-long passions – art and science. My art was happening from an early age, but the science came to me much later in life. In my art practice there are no boundaries between these two disciplines – they are truly integrated.

Drawing has been my passion and preferred mode of artistic expression since my initial art training. I was very fortunate at art school to be taught traditional drawing techniques. It was a highly disciplined process which required skills, control, patience and sharp observation of the subject. But it set me up for life.

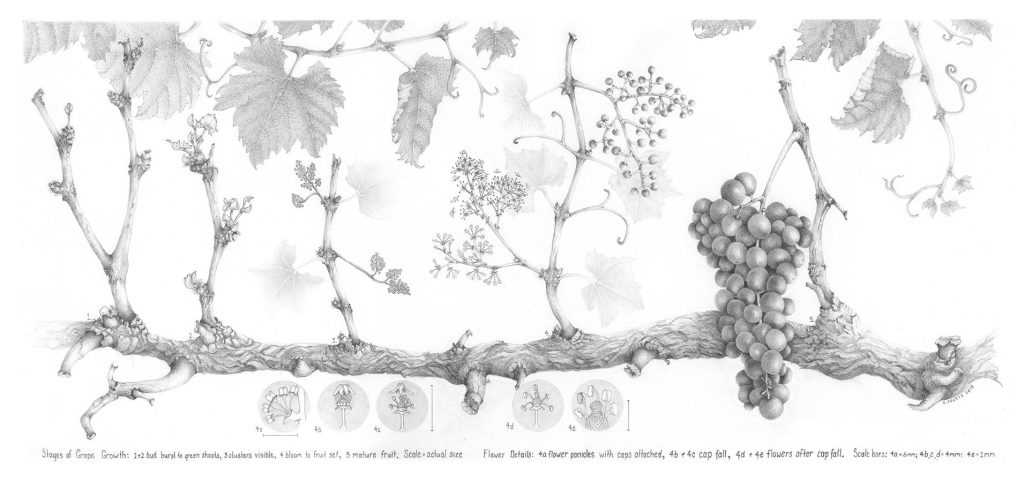

As a botanical artist I believe that all plants, no matter how humble, have a ‘story’ to tell if we pay attention. My job is to tell their ‘story’ using a visual language. In order to do that, I find I often need to make a series of images of the same plant, or several plants from a significant site, because for me there is always more to say than can be achieved in a single image. The drawing shown here, Stages of Grape Growth is such an example.

Making images of rare and threatened species is very important to me. Undertaking the drawings for the Robertson Rainforest field guide gave me a wonderful opportunity to draw plants from a critically endangered ecological community (see Gallery section of this website).

I hope that through these artworks, I can make a small contribution to help raise public awareness about the urgent need to protect and conserve our native flora.

My processes, style

and media used

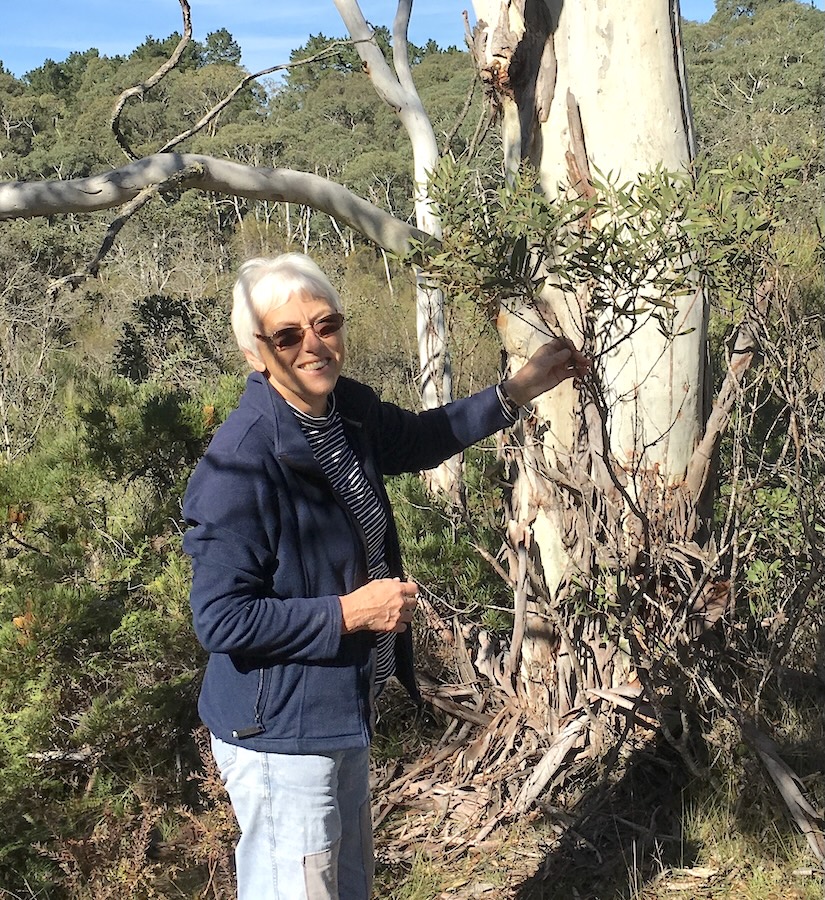

Making an image of a plant is like painting a portrait of a person. To know a plant thoroughly, so I can do it justice, I always prefer to observe it, as much as possible, in its natural growing conditions. My first step, therefore, is always observation in the field and then with a piece of the plant, a living specimen. With rare and endangered plants, I may only have my field experience to work from, so observations, sketches on-site and back up photographs are all I have available.

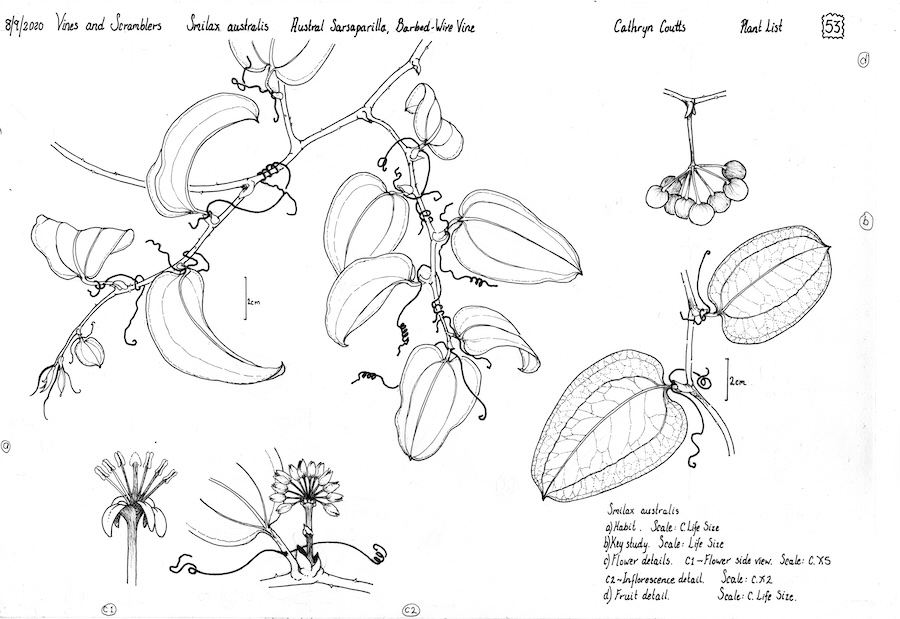

Today my artistic style ranges from a scientific illustration approach, through to more interpretative images in which I like to express the shape, line, texture and colour of plants (see Gallery). I use media such as watercolour, acrylic, pen and ink, coloured pencil, graphite and printmaking.

Once back in the studio with a specimen, I will photograph it more thoroughly, especially if there are flowers and/or fruit, so that I can accurately record the colours. I follow this straight away with some colour tests in whatever medium I plan to use, matching colours to the specimen while it’s fresh. After that, if I have enough, I take a piece of the specimen and press it, while I pin the rest up onto a display board in my studio and allow it to fall into its natural ‘habit’ shape.

It is very important in these early stages to research botanical descriptions of the plant. I familiarise myself with the scientific language used to describe such things as leaf shape, surface, size, margins, veins, flowers (male and female flowers for instance) and fruit structure. This is how I can find out details that have been observed by an expert and then go back to the plant and see those things for myself. Some important details are very small and may not be visible without using a lens or microscope. On some occasions, I have worked with a botanist who would direct my drawing by requiring me to give certain parts of the plant special attention.